We love making sure our work can be enjoyed by as many people as possible, from providing British Sign Language Interpreters to subsidised tickets. Our drive to create better accessibility is an active learning process. We regularly partner with experts, organisations and people with lived experience of disability to ensure that their voices are present in the planning and delivery of creative projects.

We want people to feel as comfortable as possible during their time with us, and we are aware that comfort looks different to everyone, which is why, in 2023, we started our series of Exploring Access workshops. These workshops are led by deaf, disabled, neurodivergent and chronically ill creatives who share their lived experiences and provide an opportunity to create action points that attendees can embed within their practice / organisations to better support those living with similar conditions.

Our first Exploring Access workshop took place in September 2023 and was led by myself and writer and facilitator David Viney. The workshop focussed on our experiences of facial palsy and body dysmorphia in an image-dominated industry. It was the first time either of us had spoken so openly about our experiences. Thankfully we had a group of supportive participants, who were ready to listen and learn.

Dave and I ran presentations explaining what facial palsy and body dysmorphia are, the ways in which the conditions affect our lives, as well as providing an insight into how current industry conditions create barriers for us. After our presentations we worked with the participants to create a set of action points to share with you, in the hopes that we can all contribute to creating better conditions for those living with facial palsy and body dysmorphia.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is a distressing psychological condition where a person becomes very preoccupied with one or more features in physical appearance, e.g. nose, skin, hair, etc. Any body part could be the focus of concern in BDD.

People with BDD engage in time-consuming, repetitive behaviours to ‘fix’ or hide the perceived flaw/s which are difficult to resist or control (e.g extensive grooming regimes, mirror checking, reassurance seeking, camouflaging, seeking cosmetic surgery etc). BDD can seriously affect a person’s daily life, including work, education, social life and relationships. As a result, social anxiety, isolation and depression are very common in BDD.

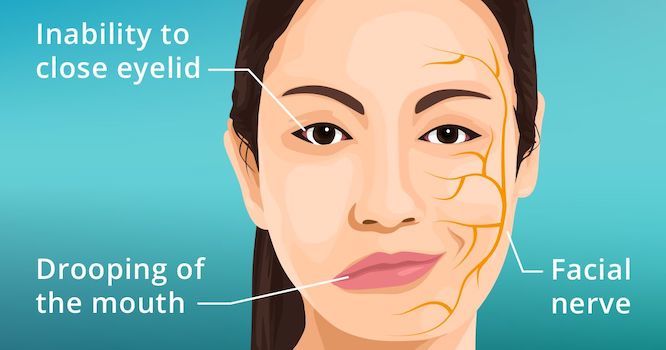

The term ‘facial palsy’ is an umbrella term which includes over 50 different medical conditions. It refers to a weakness of the facial muscles resulting from temporary or permanent damage to the facial nerve(s).

The causes of facial palsy are varied but can include infections, tumours and trauma. When the facial nerve is non-functioning, damaged or cut, the muscles in the face don’t receive the necessary signals from the brain to operate properly. This results in the paralysis of the affected part of the face.

Some episodes of facial palsy last for weeks or months. Other instances may last much longer, and some people never fully recover.

Symptoms include:

Most often these symptoms lead to significant facial distortions.

Credit to pacific neuroscience institute

People with facial palsy often experience poor mental health and can suffer from low self-esteem, depression and anxiety, and can struggle to connect with others.

The suggestions listed below were made by people who attended our workshop, including, musicians, producers, workshop facilitators, access support workers and managers, front of house staff, technicians, youth workers and medical professionals.